Org Design, Part 1: Nearly decomposable systems, with Serendipity & Slack

PART 1.

“Organizations are systems of behavior designed to enable humans to accomplish their goals” –Herb Simon, The Shape of Automation

The “buzziness” of 50-100

The period of organizational growth from 50 to 100 people can be a chaotic time. According to physicist Geoffrey West, at this stage [A] the org begins to lose its “buzziness.” Our org frameworks start to feel more reactive than proactive. We instrument policies and processes. We create layers in our organizations. But, to be successful in the long run, are we being intentional about the frameworks we shape today? Initial conditions [B] can be persistent, so having an intentional approach to org design is important early on. How can we ensure we’re putting the right structures and flows in place for regenerative growth?

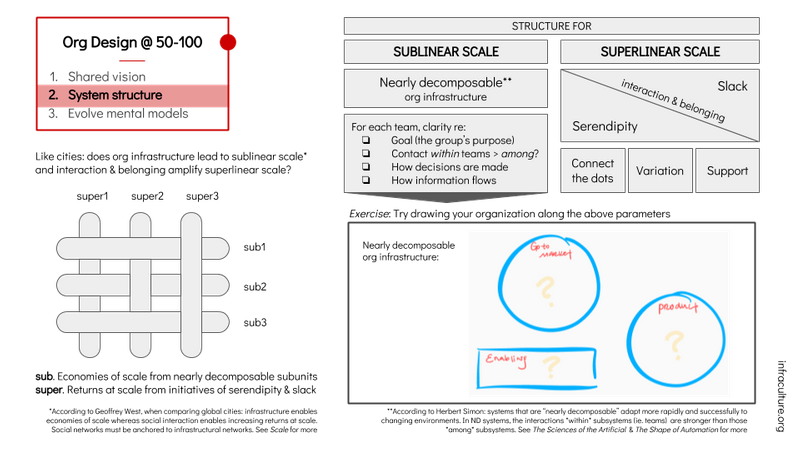

I think that strong org design requires emphasis on the following 3 things:

- Shared vision. Do all parts of the org understand what the overall goal is, and how they individually contribute to that mission?

- Systems structure. Are we set up to execute AND spur regenerative growth

- Commitment to understand & evolve mental models. Can everyone dip into the same mental model library? Is the group encouraged to update those models (individually and collectively) as time and experience go on?

I won’t go into #1 or #3 here today, although a good resource for both is Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline. However, what I do want to go into is #2: Systems structure.

***

Systems structure

As multiple systems thinkers from Donella Meadows to Peter Senge explain– “systems structure” refers to the key interrelationships that influence behavior over time. In other words, the cause of behavior in an organization lies in the structure itself. I’d like to take this a step further, to relate it to Geoffrey West’s theory of sublinear and superlinear scaling among organisms, cities, and companies.

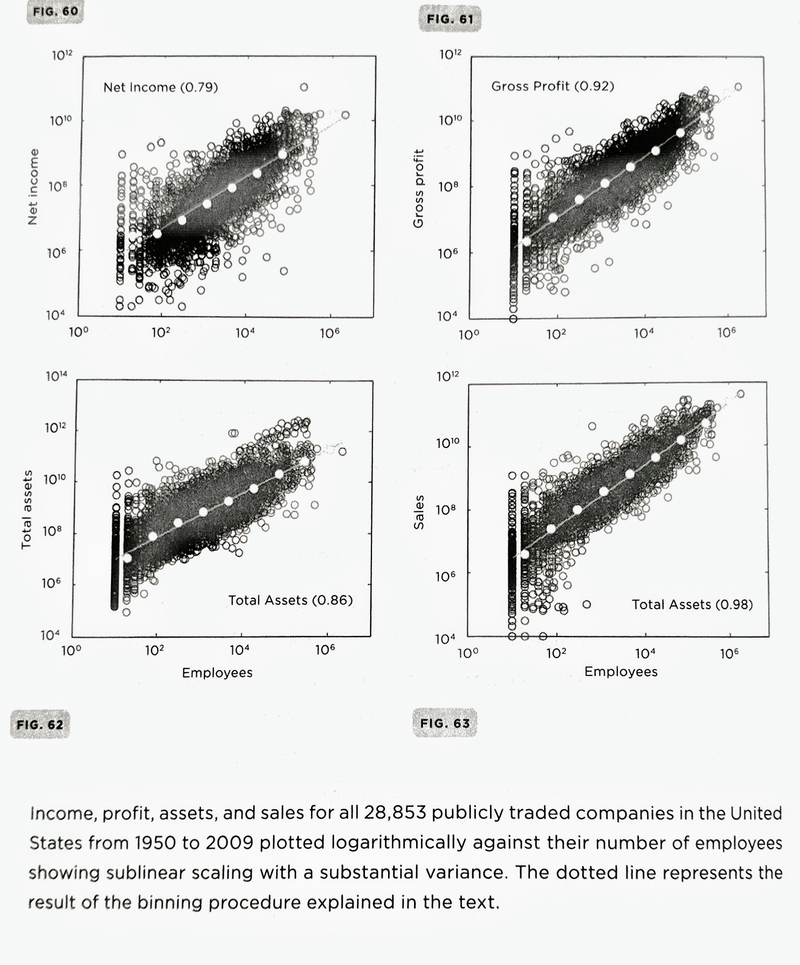

In Scale , West writes that social networks enable open-ended growth. While city infrastructure leads to economies of scale / sublinear scaling (e.g. less plumbing is needed per person as the city increases in size), the social interactions of cities enable increasing returns on scale / superlinear scaling (e.g. greater number of patents per person). Surprisingly, when applying this same framework to companies, West and his counterparts find that key metrics of companies (like sales and expenses) actually scale sublinearly. In other words, the scaling of companies resemble organisms (sublinearity) rather than cities (superlinearity). Given a finite amount of resources and sublinear scale, at some point the org hits stagnation… then ultimate collapse .

Why do most companies fail to reap the benefits of superlinearity? West laments that we do not yet have quantitative data on organizational networks within companies to fully understand. Regardless of this current lack of data though, I suspect that there is more to be found here.

What if, similar to city infrastructure, organizational infrastructure accounted for sublinear scale? And, what if initiatives of interaction and belonging, similar to the social networks of a city, could contribute to superlinear scale within a company? How should we design our organizations if this is the case?

Sublinear scale. How can we design org infrastructure that allows for dynamic efficiencies, especially given the turbulent nature of a growing organization? Herb Simon writes that Nearly Decomposable systems are most successful at adapting rapidly to changing environments. “Near-decomposability is a means of securing the benefits of coordination while holding down its costs,” Simon says, by partitioning activities based on rate of interaction. In nearly decomposable systems, interactions are tighter *within* subunits than *among* subunits. It is only at identified collecting points that information should flow between subunits, enforcing the need for greater localized decision making.

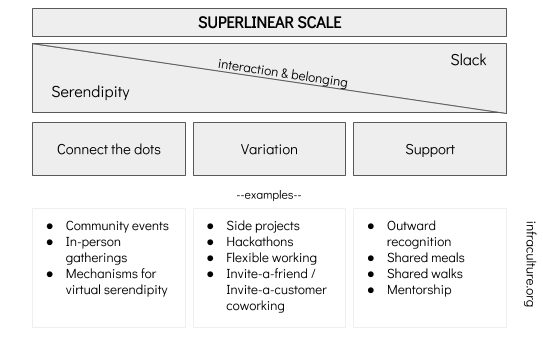

Superlinear scale. If org infrastructure can lead to economies of scale, how might we achieve increasing returns at scale? Like in cities, it is the social interactions and sense of belonging among people that can lead to this superlinear scale. While it may be hard to measure, I have a hunch that what leads to emergent growth of culture & innovation within a company— some might call it a “reset” of initial conditions–is the org’s ability to foster social interaction. Interactions that are enabled through Serendipity and Slack capacity.

When it comes to organizational structure, I find that it’s helpful to break things down as shown here:

But… with this framework outlined, what are we supposed to do about it?

***

Every organization, *especially* at the 50-100 person stage, should pause and evaluate their org design along these sub and super attributes. As with any good design activity, it’s critical to think through desired use cases and evaluate tradeoffs.

Let’s give it a try.

Are our teams Nearly Decomposable?

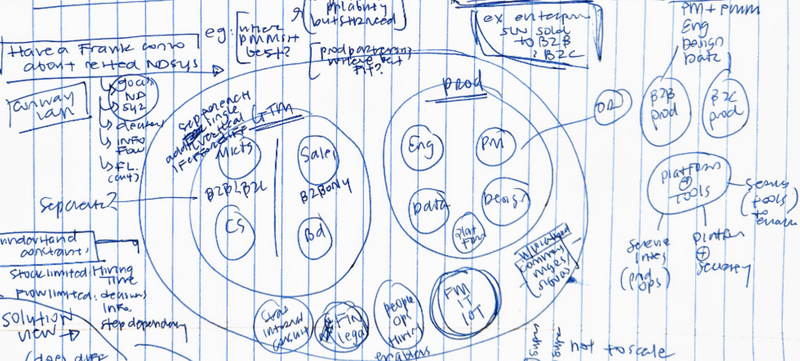

A recommended first step is to draw out your organization following a nearly decomposable framework. I’ve tried for my own organization, as shown below. For each team, ask yourself: what is its (sub)goal? What is its function or purpose, and how does that contribute to the goal of the whole? Next, think about the interactions that happen for each team… does the team interact more with others outside of their team, or more within their team? Once you’ve placed each team, perhaps in a nested framework as I show below, then ask: How are decisions made? How does information flow? Does each team understand which feedback loops it’s a part of?

This exercise is incredibly helpful to begin to understand how your teams should work together. It highlights areas to dig in deep, or it brings to light assumptions to re-evaluate. In my example below, I explore two different ways of formulating our product team: (1) with nested teams by discipline OR (2) with nested teams by project (in this case, a separation of the B2B version of our product vs. the B2C version). Another consideration illuminated by the exercise: Where should Product Marketing exist? Is PMM better as a nested Product function, where interactions happen more at the Product level? Or, do more frequent interactions happen with the Marketing team, and thus the role should sit there?

A critical point that I’ve glossed over thus far is the joint understanding of How decisions are made and How information flows. This is essential as efforts become more decentralized and localized across the org. Impacts to decision making and information flows can cause delays, which in turn impact structure. As Senge writes, “In human systems, structures include how people make decisions– the operating policies whereby we translate perceptions, goals, rules, and norms into actions.” For nearly decomposable systems to work, they require clarity around communication and decision making.

There are a handful of additional themes to consider when thinking through your org design framework:

- Nested structure. Complementary to nearly decomposable systems is the concept of nesting. Elinor Ostrom recommends “nested enterprises” for commons that are a part of larger systems; she refers to this structure as polycentric governance. Similar to Herb Simon’s watchmaker parable, nested subunits allow for greater stability across the whole.

- Understanding constraints. Constraints can either be stock limited (such as hiring), or flow limited (related to decisions, information, or step dependencies). Make sure to ask yourself: what constraints exist, and how do they impact decision making and information flows?

- Conway’s Law. According to Conway’s Law, products are a reflection of the organizational communication structures that produce them. Employing this concept is helpful when evaluating whether subsystem efforts should be “project-based” or “team-based.” For example, say your company produces a product with two separate interfaces for the same solution (think of the Uber Rider app vs. the Uber Driver app). You may be best served by structuring your teams to match the split of these audiences, otherwise risk confusing your users. The same evaluation should be applied as your organization moves to new verticals, too.

Do we foster Serendipity and Slack?

Where sublinear attributes bring economies of scale, superlinear attributes bring greater returns with scale. As with cities, could social interaction and sense of belonging contribute to open ended growth in a company? I like to think of this benefit through the initiatives of Serendipity and Slack. Both allow for variation in one’s personal workflow, a unique opportunity to “connect the dots” on disparate ideas, and the time to offer (emotional) support to oneself and others.

Serendipity. Initiatives of serendipity have long been written about in the context of groups. We’ve seen stories of crowded corridors (Bell Labs) and multiple disciplines under one roof ( Building 20 at MIT). In the city, we think of them as something overheard in a bustling coffeeshop that triggers a new solution to a persisting problem, or as a chance encounter on the sidewalk. In these cases, the physical world does the heavy lifting for us; the proprietor of time schemes so that multiple people find themselves in the same area at the same time. For our purpose here, serendipity = the unexpected encounters between people at an organization, encounters that transcend nearly decomposable systems, often with no immediate relation to work at all.

Slack. “Slack” is kind of like the best ideas happen in the shower heuristic. Performing a rote exercise (like taking a shower) in a varied environment (surrounded by water) gives us mental slack to put attention to new ideas. At the 50-100 people org level, it’s what fills the role of innovation and R&D centers at bigger companies. (Centers, according to West, that companies kill off too soon, at the expense of their ultimate demise.) Slack is what 20% projects are made of. It’s where we might put longer term projects. Empathetic slack is the capacity to provide support to ourselves and others. How many times have I seen a colleague burn-out while personally feeling just as much “at-capacity” myself that I didn’t provide the real time support they likely needed? Similar to the theory of constraints, if all system components are at capacity, there’s no longer “give” to deal with changing environments.

So… now what?

Just as you outlined your organization above, think about the ways in which your company celebrates moments of Serendipity and Slack. The examples above are not exhaustive. Recognize the importance of these initiatives, and fight to keep them and grow them. Some of the more obvious activities include hackathons, community events, and shared meals. A less obvious one is working in changing environments to prompt variation. One idea I’ve been brewing for quite some time is Invite-a-friend coworking.

Nat at GitHub has a different spin on this: Invite-a-customer coworking. Still another: How can we use the virtual tools at our disposal, coupled with our built environment, to better simulate the serendipitous events of real life?

Note: Initiatives for interaction and belonging (via social networks) likely cannot work on their own. Just as the social interactions of cities are dependent on a “direct and necessary coupling to the grungy reality of the physical world” (i.e. city infrastructure), the social interactions of companies are long-run dependent on effective organizational infrastructure. Superlinear scale is dependent on the success of complementary sublinear scaling components.

Take advantage of initial conditions

So, how can we ensure we’re putting the right structures and flows in place for regenerative growth? We might not yet have the data to understand superlinear scaling opportunities for companies, but should that prevent us from experimenting? Nope. Org design should consider attributes related to *both* sublinear and superlinear scaling. For economies of scale, Nearly Decomposable systems have the most promise to deal with changing dynamics typical at a growing firm. For increasing returns at scale, fostering interaction and belonging through initiatives in Serendipity and Slack is the way to go. And, there is still more to be uncovered. Truth of the matter is: most organizations do *not* have metrics for these kinds of sublinear and superlinear scale. New ways to measure organizational structure and interaction, without dampening growth through cost of measurement , are an exciting new arena.

Of course, it is one thing to *say* all of this, and quite another to *operationalize* it. Especially when you don’t have structured authority to do so…That’s for Part 2, coming soon.

APPENDIX

[A] Company scaling from Scale by Geoffrey West

Notice that from 50-100 employees, scaling is superlinear (with high variance). I’ll ignore for now that this data is from publicly traded companies (and so data for less than 100 employees is likely limited!)…

[B] More links on Initial Conditions:

- Multiple discussions on initial conditions in The Evolutionary Foundations of Economics

- Herb Simon on initial conditions in The Sciences of the Artificial

- Evidence of initial conditions relative to city infrastructure

- City siting

- Spatial structure

- Opportunity to reset initial conditions, from West et al